The Urban Naturalist: Cities, nature, and education

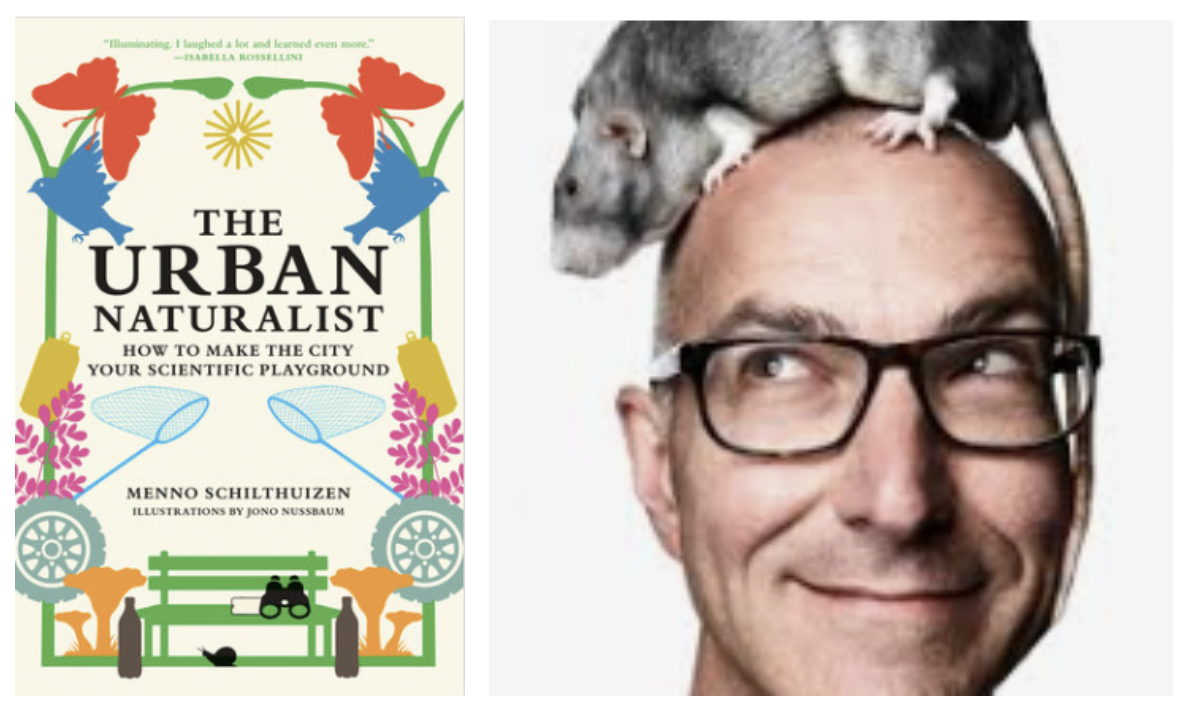

Welcome to The Remake’s first book recommendation: Menno Schilthuizen’s The Urban Naturalist: How to Make the City Your Scientific Playground (MIT Press, 2025). Menno, a professor of evolution and biodiversity at Leiden University, has written a playful, informative, and thought-provoking book about the non-human residents of cities and our relationship with them.

You don’t have to take my word that The Urban Naturalist is worth a read. Film star Isabella Rossellini puts it well:

I find science fascinating, but laughing is my favorite activity. Menno presents scientific facts with his absolutely irresistible humor. Reading his book is illuminating. I laughed a lot and learned even more.

The scope of The Urban Naturalist is far ranging. Menno shares the story of Mary Treat, a 19th century "amateur scientist” whom he considers a forerunner to today’s citizen scientists. He explains the joy of creating a bug collection. He details research on the hazards of roads to wildlife. This is just the tip of the iceberg.

Menno introduces us to a microbial mat in Paris that is home to over a thousand organisms, and a church in Rio de Janeiro whose facade is covered with over 100,000 different species of algae, fungi, and bacteria. Yes, you read that correctly: 100,000. It is partly because of places like these that Menno calls the city a “naturalist’s gold mine.”

The city as a naturalist’s gold mine? This certainly changes how many view urban environments. The shift is an important one, and seeing cities through Menno’s eyes raises two important questions for educators who aim to build children’s solidarity with the rest of nature:

- How should we talk to children about the plants and animals that we share our cities with?

- How should an understanding that cities are unique ecosystems influence “nature” education?

In this essay I explain how The Urban Naturalist raises these questions and provide preliminary answers to the two questions.

How should we talk to children about the plants and animals that we share our cities with?

We adults influence children’s relationships with the rest of nature, in part, by the language we use. Through our words we often characterize the plants and animals that we share our cities with as friends or foes. In a chapter titled “The Accidental Ecosystem” Menno makes two points relevant to the question of how to talk to children about urban ecosystems. The first is that urban ecosystems are an interesting amalgamation of native and non-native species. The second is that the common and value-laden descriptions of non-native species as “invasives” is unscientific and, in urban ecosystems, wrong-headed.

Menno begins his explanation in Serbia, and the reaction to the introduction of the brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys) to Belgrade. Native to Asia, the half inch long insect with an attractive mottled pattern on its back, traveled the world on agricultural produce and passenger luggage to reach a new home.

The bug has not received a warm welcome in Belgrade. Media outlets have decried that the city is “under attack” from an “army of invaders.” A tabloid headline blared “STINK BUGS FROM CHINA ATTACK!” Misinformation has been spread, with a webzine claiming the bugs “suck blood.” Not true.

Such inflammatory rhetoric is not the exclusive province of Belgrade. The use of militaristic, xenophobic terms is common in describing non-native species that have spread around the world as a result of human behavior (trade practices and the degradation of local biodiversity which could provide checks on new arrivals).

Is the introduction of species like Halyomorpha halys bad? What does the science say? In isolated ecosystems (e.g., islands, mountain tops, lakes), generally protected from new competitors, with simple food webs, and low biodiversity, the introduction of new species can be disastrous.

Cities are very different ecosystems. Urban areas are in a constant state of disruption (from development and human-created pollution). Often new species can be more suited than natives for changing conditions. As Menno explains:

Urban ecosystems are ecologically very different places from pristine natural environments. The rules and practice of nature conservation have been developed in such wild places but do not always apply to cities equally well. In short the urban ecosystem is not a place where we should be combating exotic species. Rather we should embrace them as essential components of the churning fermenting mix of ingredients that together make up the novel ecosystem that is evolving among us in our cities.

He adds, given the stresses of urbanization, “Plants and animals that survive and thrive [in cities] should be celebrated.”

And it is not just non-native species that receive negative descriptors. It is not uncommon for native animals that live in cities to be referred to as “pests”, native plants as “weeds,” and places in cities where biodiversity thrive as “overgrown” and “unkempt.”

What is an alternative rhetoric? Educators in Australia, drawing on Aboriginal practices and post-humanist thought, are describing the rest of nature in a different way. They talk about the species they share their space with as kin and family. When taking a walk, rather than asking the children “what will we see” or “what will we discover” they ask “who will we meet?” Specific critters are referred to as he, she, or they rather than it.

In this characterization, it is important to remember that members of a family don’t always get along. The educators are not telling children not to swat a mosquito. But with family there is a sense of solidarity and a desire to find solutions that accommodate everyone.

A word of caution. Changing language takes time and patience. No matter how well-intentioned or technically correct, attempts to mandate shifts can be counterproductive. Demands for immediate adoption produce backlashes. Thoughtful explorations are essential.

In this spirit I note that describing the stink bug as a “cousin” is scientifically more accurate than calling them “invaders.” After all, we share a common ancestry with stink bugs, and half our DNA is in common.

How should an understanding that cities are unique ecosystems influence “nature” education?

Nature education for city kids generally involves taking them somewhere–to a garden or park or on a field trip to the countryside–to encounter the natural world. Chapter 15, “On the Origin of Urban Species” and Chapter 16, “We are a Node” raise a provocative counterpoint to the idea that we have to go somewhere else to find nature. Menno explains that, like rainforests, deserts, and tundra, cities are unique ecosystems. Here, humans are the keystone species. The question of how an understanding that cities are unique ecosystems should influence “nature” education is one I am just beginning to grapple with.

Chapters 15 and 16 are fascinating reads. Menno begins Chapter 15 with a story about the anoles lizards of Puerto Rico. Researchers have found important differences among the city and forest dwelling members of this species.

The feet of urban anole have longer toe pads and shorter, straighter, wider toenails than their rural relatives. These adaptations are better suited for the rain pipes, gutters, tile floors and other smooth surfaces of the human-made environment in which they are evolving.

Smooth, impervious surfaces are just one difference between urban and rural areas. Cities are hotter, noisier, and brighter (especially at night) than the nearby countryside. The results are physical changes in a host of species. Researchers have found adaptations in urban dwelling snails, ants, spiders, and dandelions.

The fact that humans bring food from afar into cities is another element that sets cities apart as unique ecosystems. Menno explains:

Humans are an important node in the network of ecological relationships in the city. In fact, we are a keystone species, without which large parts of the urban ecosystem would collapse. Directly or indirectly, intentionally or involuntarily, our food feeds many other species in the natural fabric of the city. This may be in such an obvious way as someone feeding bread to the ducks in a park pond or in more discreet, visible ways such as sewage leaks that feed the city's soil microorganisms. Either way, the omnipresent Homo sapiens is a central species in the maintenance of urban biodiversity. Removed from nature as we may think we are in our glitzy urban environment, we are actually much more entwined in it than in most nonurban places.

Even when they are not in parks or gardens or on that field trip to the countryside, city children are in an ecosystem that involves countless of entangled species. I need to sit with this provocation and welcome the chance to discuss it with others to sort out the implications. I end this essay with one possible implication, a story of how two of my colleagues at Newtowne School have renamed the walks they take with children as “urban hikes.”

“We are so lucky”

Last fall Blue Otter classroom teachers Jen Schreiner and Danielle Hart noticed their young four-year-olds’ interest in the hiking stories that Jen was telling during snack time. The tales, about Jen’s adventures in New Hampshire’s White Mountains and the Pacific Crest Trail, prompted calls for “Hiking story! Hiking story!” The children were fascinated by the idea of being out in the wilderness, encountering wildlife, and eating trail mix (which in Jen’s stories, features chocolate).

While a field trip to the White Mountains was not a possibility, what about “hikes” in our city? While people do not flock to Cambridge for its natural scenery, Jen and Danielle realized that we have trees, squirrels, and birds along with our many cars and buildings. The idea of urban hiking was born.

The teachers procured child-sized backpacks. They discussed with the children what was needed for hikes. It turns out, according to the children, a first aid kit, a phone in case of an emergency, water bottles, and trail mix with chocolate are required. Then off they went into the city.

The children took their backpacks as these were hikes rather than walks. They encountered wildlife, statues, and other people. They made maps to guide them on their adventures. They were out in an urban ecosystem and had adventures.

On one of these hikes Tymon declared, “We are so lucky to have so many beautiful places to walk to.” I appreciate that Tymon saw our urban space as beautiful. I agree with him. At Newtowne we are lucky to have such an exciting ecosystem to explore. We are fortunate to be able to follow our children’s interests when we plan our curriculum. And we are lucky to have The Urban Naturalist to provoke our thinking.

Thanks to Liz Merrill, Jen Schreiner, and Danielle Hart for their comments on this essay.