The world is burning and they are telling me how to use a fire extinguisher

Four principles of meaningful early childhood trainings

In response to being subjected to my state’s required 12 hour online course for early childhood educators, this essay outlines four principles of meaningful training.

Massachusetts’ “Strong Start” training

Every early childhood educator in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is required by the state’s Office of Early Education and Care (EEC) to take Strong Start, a 12 hour online training course. The course is broken down into 13 modules that include: Safe Sleeping Practices, Medication Administration, and Transporting Children Safely.

Here is a flavor of the training. In the first module, Emergency Response 2.0, there is a 32 second segment on “Using a Fire Extinguisher.” As a slide appears on screen a soft spoken female voice explains:

Staff in your program should be trained in how to use a fire extinguisher. Remember PASS to properly use a fire extinguisher. Pull the pin. Aim low at the base of the fire. This is where the fuel typically is. Squeeze the lever. Sweep from side to side. Watch for reignition and repeat if necessary. Now that you understand what emergency supplies must be available at all times, you're ready to learn about another requirement: an emergency action plan. Select next to continue.

Bored yet? Perhaps not. But imagine hundreds of such slides and thousands of clicks (some slides required multiple clicks), over the course of 12 hours. To put this time requirement into perspective, if this would have been an in person experience, it would have stretched over almost two work days.

Of course I am supportive of the stated goal of the course–keeping children safe. But I question the training's effectiveness. I found the experience infuriating, and being angry is not a state of mind conducive to learning. From my conversations with colleagues, I learned I was not alone in periodically cursing at the screen in frustration..

So I decided to turn lemons into lemonade. Knowing I would be chained to my computer for hours on end, I used the course as a counterpoint and came up with four principles for meaningful online training. I offer them here to those who aspire to provide effective (not alienating) training for the early childhood educators. I also write for my thousand of colleagues in Massachusetts who were subjected to the training. Perhaps we cannot change our Kafkaesque bureaucracy, but at least we can laugh at it together.

Principle 1: Use a proven theory of learning

The theory of learning deployed in Strong Start is, “Say it and they will know it.” It is a transmission theory of learning best described as a knowledge dump. Quick, what are the four steps for using a fire extinguisher? You read them less than 30 seconds ago. Will you remember them tomorrow? In two weeks? In two months? Most importantly, in a stressful situation, an actual fire, would you remember them?

To accurately answer if you would remember PASS (or what PASS stands for), you need to know that the information was embedded among thousands of other bits of information. There is a lot of information delivered in the training. I mean A LOT. The training has over 50 learning objectives.

The crown jewel of the Strong Start approach to learning is the final module on child development. The module presents three ages (infant/toddler, preschool, school age), each broken into sub-categories (e.g., preschool into 3-year-olds and 4-year-olds), with four domains of learning (language, social/emotional, cognitive and physical). For each age subcategory, 3 to 8 “milestones” are shared for a total of 223 factoids (e.g., a 18 month old social/emotional development includes fear of strangers; the 10 to 12-year-old “enjoys using the phone”). Ignore the random feel to this information (e.g, why one of the four most important things to know about a 10-year-old’s cognitive development is that they enjoy using the telephone). The math tells us that learners have about 12 seconds to process each factoid (divide the 45 minutes devoted to the 223 pieces of information). Who thinks anyone will remember much of anything?

An interesting twist to this transmission model was the belief that if information is stated two or three or four times it will be better remembered. Perhaps. Or more likely, knowing one will have stuff said again and again, listeners will space out. Colleagues have told me of taking the training with another device open to Netflix. I know an educator who had her teenager take the training for them.

Two suggested alternatives to this approach. The first is called “just in time learning.” It is based on the notion that people will take in information when it is important and relevant to them and ignore it when it is not. For example, while fires are rare in early childhood centers, they do occasionally occur. I am skeptical whether anyone who took the training would remember the expansive bureaucratic requirements if a fire did occur at their center (e.g., the agencies to notify). I am sure they would remember all the information if they were provided it after a fire, when they would need the information.

The second is to be straight with educators. Explain, “We have some really important safety information. We are going to share it with you as efficiently as possible. Please pay attention.” I am confident I could pare down the time of these training sessions by more than half, a more reasonable amount of time for people's attention spans.

Let’s return to the “Child Development” module and analyze a slide regarding the milestones of a five-year-old's physical development to give you a sense of the knowledge dump feel of the training. Note, these nine milestones were all described in less than a minute.

Now attend to the content. What do you notice? Sure, they got some things right. Hopping and climbing belong in the realm of physical development. But “demanding and sometimes cooperative”? This is social/emotional development. And “Telling what’s real and what’s not.” For the life of me, I cannot figure out how this is considered physical development. It isn’t. The ability to tell what is real and what’s not is a cognitive skill. It is like saying a buffalo is a bird or the Boston Celtics are a minor league baseball team. This is a clear category error. Which leads me to the second principle.

Principle 2: Provide accurate information

Everything in a training course should be accurate and true. But this is not the case with Strong Start. Here are our three additional examples.

- Not every toy needs to be accessible to children.

Throughout the Strong Start course there are periodic “knowledge checks”, where my colleagues and I are given a scenario and told to evaluate it. In the Physical Premises Safety 2.0 module one such knowledge check begins:

Space is limited, so some books and toys are stored on high shelves and in cabinets. Does this meet safety standards? Yes. No.

Of course, yes. Best practice in early childhood centers is to make toys available to children in organized and inviting ways (crowded shelves being anathema to this approach) and to rotate what is available for children to use to maintain engagement in materials. But according to Strong Start this is, “Incorrect. Toys should be accessible to children, so it's a good idea to place them on low shelves.”

What could this even mean? Put all your toys on a child level, even if the shelves would be crowded and difficult to use? Only have the amount of toys that fit onto low shelves and get rid of the rest? In the 1980s one of my favorite bands, the Talking Heads, had a song titled, “Stop Making Sense.” A catchy tune, but not an educational principle. And I’m pretty sure David Byrne was being ironic.

- Acorns are not potentially dangerous tree nuts to be avoided.

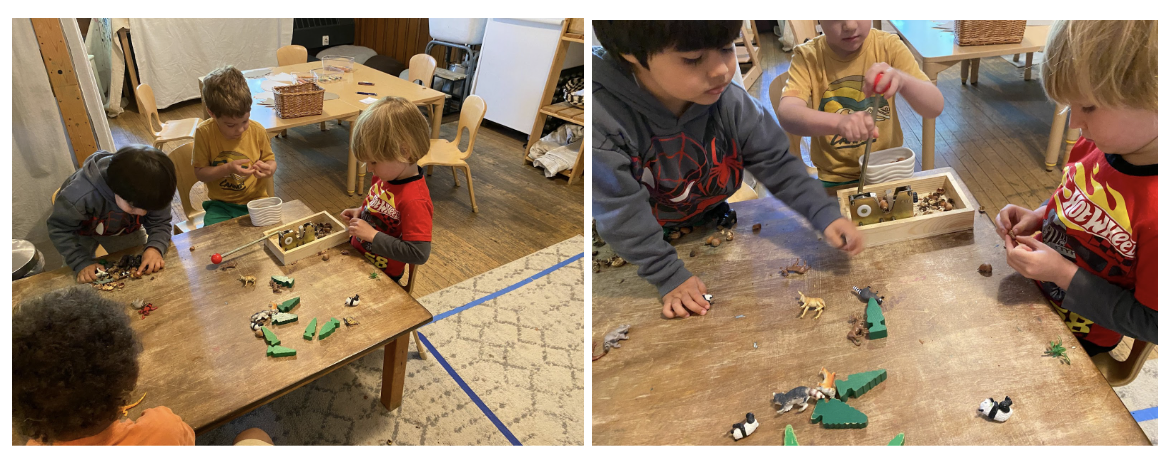

I call this out after watching numerous learning experiences such as the following. Four four-year-olds are gathered at a low table in my studio. Two are creating stories using animal figurines. Two are taking turns using a nutcracker to open up acorns.

The following is overhead:

-Here is more food for your animals Alejo.

-I’m finishing this acorn off.

-My turn. OK.

-These acorns are chocolate flavor.

-I have food for every animal.

-It’s cracking.

-Look at this humongous crack on this acorn.

-It cracked in half. That was so cool, wasn’t it, Bo?

The conversation proceeds for more than 20 minutes, a significant amount of time for children of this age to stay focused on one activity. Such sustained interest in cracking acorns is common. Among children at Newtowne of all ages, using the nutcracker is a favorite activity. Children observe the acorn meat and speculate about the differences among acorns. In the fall, they find acorn weevil grubs, leading to conversations about these interesting insects. The play promotes language development, scientific skills, and turn taking. And acorns are abundant and free in Cambridge.

But I know of programs where acorns are banned. There is a misconception that acorns, as a tree nut, can be a dangerous allergen akin to walnuts, cashews, and pecans. The medical evidence says otherwise. The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of American explains:

Acorns are botanical nuts of oak trees. They are not a common allergen. Anaphylaxis (a severe allergic reaction) due to contact with acorns would be very rare. There are case reports in the medical literature of allergic reactions after eating acorns. This was thought to be caused by cross-reactivity due to a pollen allergy and not due to nut allergy. Contact with acorns would pose a low risk of systemic reactions, even in someone with a tree nut allergy. Washing with soap and water would get rid of the allergen.

Strong Start’s Food Safety module tells of the eight most common alergines (e.g., shellfish, peanuts). The list includes tree nuts (e.g., walnuts, pecans). These nuts can pose a very serious risk with children allergic to them. That is why Newtowne School has a no nut policy. But rather than an image of a walnut or pecan, the icon representing tree nuts in Strong Start are two acorns.

The icon clearly perpetuates the misconception that acorns can be dangerous and are to be avoided. Lets not have such misconceptions deprive children of valuable learning experiences.

- Stop teaching children to be afraid of strangers.

The most disturbing misinformation of the course is found in the Missing Child Prevention module’s section on field trip supervision. Educators are told that when on a trip to a local park or other location, if someone unknown interacts with a child, “You should notify the police.”

What?! Without a doubt, there are creepy people out there from whom we need to protect our children from. However, the vast majority of people kids will meet on field trips are kind, interesting people; fellow citizens of their communities.

The Harvard philosopher Danielle Allen writes in her book, Talking to Strangers that in the U.S. we do have a civics curriculum for young children: don't talk to strangers. Her book is an eloquent rebuttal of this “curriculum”, explaining that in order to overcome the current polarization and anti-democratic shifts we need to develop “political friendships” where the welfare of people we do not know is important to us.

A seemingly unintentional pearl of wisdom in Strong Start appears in the Child Development module during a video about young children’s “stranger anxiety.” A caregiver tells a crying 18-month-old, "You are going to meet new people everyday.” True, and what should we teach children to do when this occurs? Treating people who children meet on field trips as fellow citizens, who we say hello to and treat with courtesy, is an obvious step to help children develop a sense of political friendship. Treating those people as threats, requiring a call to the police, undercuts any efforts to develop the sense of trust in our neighbors that democracy requires.

Early Childhood professionals are smart. We can tell the difference between someone who poses a danger to our children and someone who is safe. Which leads to my third principle.

Principle 3: Treat early childhood educators with respect

SIDS (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome) is a tragic event. It is vital for the people who care for infants to know about SIDS and how to prevent it.

But I do not work with infants. None of my colleagues at Newtowne do. Nor does our program transport children via car, bus, or van. Yet all 20 of us were required to take training modules on these topics. Nearly 40 hours of people's time was spent on topics which have no relevance to our jobs.

There is an easy fix here. When registering for the course participants should share the ages of children they work with, the type of program they work at (center based, family child care), and other characteristics of their workplace (e.g., whether their program provides transportation for children). A relatively simple algorithm could then tailor what modules the educator should take. A more insidious form of disrespect in the Strong Start training was the tone of the “instructor.” When one answers a knowledge check question correctly she calls out in a overly friendly tone,

“Great job.” After hearing “great job” several times I began thinking: where had I heard someone say “Great job” in that tone. Then it struck me. I had been saying that. But not to human beings. My son and future daughter-in-law had gone on vacation and my wife and I were taking care of their two dogs. “Great job, Jasper. Great job, Roly” was coming out of my month with regularity. Fine for a canine, not for early childhood professionals. It saddens me to have to write this.

Principle 4: Address climate change

The last ten years have been the hottest in recorded human history. Climate change is causing devastating wildfires, stronger hurricanes, rising sea levels, and more frequent droughts. The science is clear. Temperature rise is baked in; even if we stopped emitting carbon today we face another thirty years of rapid climate change. The political and social upheavals that this will cause will be unprecedented. As the courageous climate activist Greta Thunberg explains, “The house is on fire.” Yet there is not a word in the Strong Start training about the subject. Nor is there anything in the training about anti-bias work, about promoting literacy, or supporting children’s metacognitive development.

Time is a precious commodity. A common refrain I hear from my colleagues is the desire for more time to plan, reflect, and learn. The Department of Early Education and Care has taken a day and a half from every early childhood educator in the state. Time that could have been spent thinking about the implications of climate change for teaching young children. Or any number of important tasks.

But it’s not funny

I hope you found this rant entertaining in a dark comedy sort of way. But the situation is not funny. Not funny because the training contributes to the deprofessionalization of early education, wastes thousands of hours of precious time, and exacerbates the alienation of citizens from their government.

The training is not funny because it perpetuates an impoverished and discredited pedagogy at the very time more empowering and playful pedagogies are needed. My Remake co-editor Amos Blanton captures the tragedy here when he comments:

A key aspect to the destructive nature of this pedagogy is that it is totally blind to what the learner knows already or is interested in. I think that's often the case in schools where the teachers don't have time to listen to and get to know learners. In both of these situations, an institution is trying to get something checked off of a checklist, and shift responsibility from teacher to learner, the logic being "We said it three times, so if they didn't learn it, then it reflects on their lack of intelligence." It's a kind of epistemic imperialism that does harm even when the institution’s intentions are to teach something important.

He continues, writing to me:

Isn't your experience here very similar to that of a lot of kids in conventional compulsory schools, who are repeatedly told useless and uninteresting information they don’t care about, without any meaningful context? This behavioristic pedagogy is at the root of the failure of education more generally today, and the political crisis it has helped create. You had to stand it for 12 hours, but the kids have to stand it for years.

Yes, the kids. The most important reason none of this is funny is the kids, who are growing up in a time of rapid climate change. They desperately need educators who can prepare them to face challenges we cannot imagine. Educators who need support in being more creative, collaborative and adaptable. Educators who know more than how to use a fire extinguisher.

Thanks to Amos Blanton and Liz Merrill for their comments on this essay.

I want to believe that there are examples of training that use a stronger model of learning, are accurate, and treat educators with respect. If you know of an example, please let me know so I can highlight it here on The Remake.