Solarpunk Futures: Playing towards a Sustainable World

Lately, leaders in the movement to address climate change have described our current malaise as a crisis of the imagination, by which they mean it seems hard for us to collectively imagine and move towards a better, more sustainable future. Imagining sustainable futures is difficult because the causes of the climate crisis are deeply interwoven with our politics, our history, and our daily needs and desires. To come up with a plan to resolve all this complexity feels overwhelming, which is why we need to play with it.

As part of Playing with the Sun, I've been developing a creative learning activity called Solarpunk Futures, inspired by a genre of science fiction that imagines a just and sustainable world after the climate crisis is resolved. In my work as a play designer and researcher, I've noticed that when people play together new and interesting ideas often emerge. These rarely arrive in the form of immediate solutions, but are often valuable in many other ways. Creative play tends to reveal what's interesting and important to the players, similar to the way art reveals what's interesting and important to the artist. That awareness helps set the stage for future breakthroughs.

Developing a shared sensitivity to what a community values is an important aspect of collective creativity, something that the artist Brian Eno calls Scenius - by which he means the genius of the collective "scene", as in an art or music scene. In the early days of the Scratch programming community, a project of the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at MIT Media Lab where I ran the online community for 6 years, a lot of the creativity and learning we saw was driven by sub-communities who were interested in one genre of project or another. Scratch was the first blocks-based programming language, designed to enable kids to make games, animations, or whatever type of project they can imagine. The online community is a place to share projects made with Scratch and talk about them in the comments. Children who loved role playing games inspired by popular fiction would constantly invent new characters and scenarios. And those who loved platform games would invent and share technical and aesthetic strategies for making better games. Each genre had its own "scene" or sub-community of enthusiastic creators innovating at the cutting edge, just as one finds in a vibrant art or music scene.

There's a lot of interesting research on collective creativity looking at the role played by groups in innovation. Much of it questions the commonly held assumption that good ideas come from individual geniuses. More often, good ideas emerge out of groups of enthusiastic people working or playing together - just like what we saw and still see happening in the Scratch community. So instead of continuing to focus education on individual learners, educators need time to explore how to create better conditions for this type of "Scenius" to occur around meaningful and important topics. And few topics are more important today than figuring out how we can learn to live sustainably.

Playing together towards Sustainability

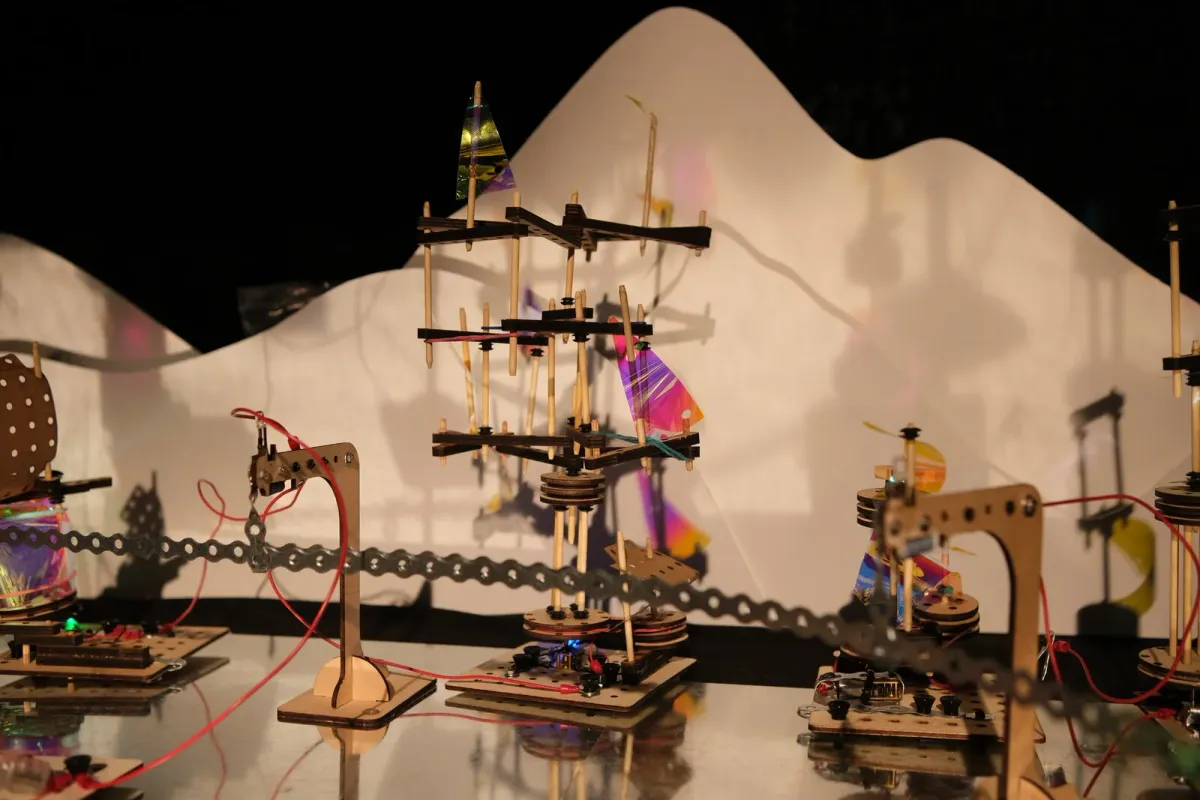

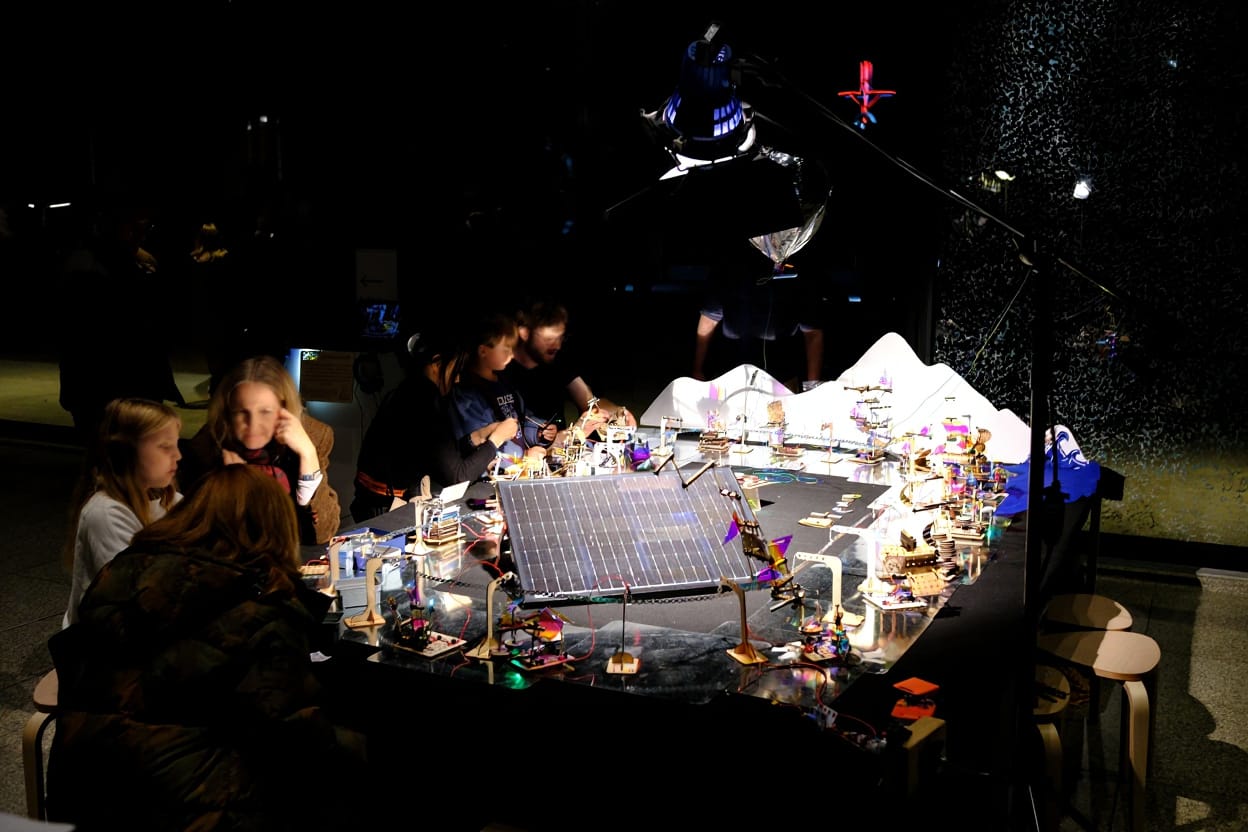

Solarpunk Futures is the latest Playing with the Sun activity designed to create the conditions for both creative learning and a brief form of “Scenius” to occur. It invites participants to build something that represents what they wish to see in a sustainable city of the future. The model city is powered by a working solar-powered microgrid designed to be modular and extensible, so educators and tinkerers can shape things however they wish. While playing with it they develop both a sense for how sustainable energy works and the characteristics of energy networks. Like all Playing with the Sun activities this one is open source. Detailed building instructions are available on the Playing with the Sun website, so other educators and researchers can make it themselves and adapt it to suit their needs.

Solarpunk Futures debuted at the Festival of Future Nows at the Neue Nationale Gallery in Berlin, with the artist Andrew Amondson acting as creative producer and co-facilitator, and contributing to the design. It functions both as a collective artwork and a creative learning experience that interested people are invited to drop-in and try. Over the course of two days, around 100 people between the ages of 5 and 85 sat down to build projects, and about 20,000 viewed the collective artwork as it emerged.

When people expressed interest, we explained that we're building a sustainable city of the future together, and if they like they can build something that represents what they wish to see in that future. While they waited for a seat to open up at the table, we asked them to watch videos of what previous contributors made and their descriptions of what they wished to see in a sustainable future. Participants were allowed to build for as long as they liked (usually between 15 and 45 minutes), after which we made a recording of their build and their description of it, and added it to our collection of documentation videos playing on a screen on a plinth with headphones. The reason we asked new participants to begin by looking at what earlier participants made is to help spark their imagination and set the stage for cross-pollination of ideas. Good ideas can be contagious, and sometimes this leads to the emergence of collectively creative patterns or themes in collective play. At Newtowne school, they call this Good Ideas from Good Ideas.

Looking at the data collected from around 100 participants and 43 builds over the course of two days in Berlin, we can see four emergent themes. About a third of the projects were about Sustainable Infrastructure and Utility, a type of project I provided several examples of at the beginning. Another third were about Mobility and Exploration, enabling people to travel and across the earth and through space. The remaining third was split evenly between environments that support Socializing and Play, and a grab-bag category of Abstract and Aesthetic concepts.

As long as a creative learning activity is sufficiently open-ended, the projects will reflect the interests of the participants - in this case, adults and children attending an art festival in Berlin. The category that was most surprising to me was Socializing and Play Environments. There were playgrounds, climbing gyms, dance halls, a gym with an integrated circus, even a football clubhouse compete with a record player and pizza oven. They seemed to express a desire for a future with places to play, to relax, and to be physically together, sometimes across generations. Perhaps this was motivated by a weariness with computer-mediated socialization.

The Art of World-Building

In her piece To Build a Beautiful World, You First Have to Imagine It, the climate author Mary Annaïse Heglar wrote:

At its core, world-building is what it sounds like: the process of creating an imaginary world for a work of fiction. It’s the practice of taking the ideas in your head, the sensations from your imagination, and allowing people to see what you see, feel what you feel... It’s an art, not a science.

In Solarpunk Futures, we invite participants to practice the art of world-building together, not only with their imaginations, but also with their hands. We provide a simplified version of an electrical network and loads that depend on it, which exposes them to a technological "grammar" that mirrors what we'll need in a sustainable future. But the goal is much more than to develop their technical literacy. It's to invite them into a shared, collective conversation about what's possible, and to demonstrate how what they imagine could become part of a collective vision for the future.

What effect does this have on the participants? Creative learning experiences don't tend to respect disciplinary boundaries between art, science, and education, and can be very difficult to measure. I saw lots of curious faces, both young and old, and many seemed excited by what they'd seen, created, and shared. But we can't say definitively what the long term effects of this kind of play are. In my view, learning to collectively imagine and play toward a better future is like any other muscle or skill. It must be exercised in order to grow stronger.

This type of design research requires iteration, with many people in many locations, and this was only our first run. Several practitioner researchers are already planning to build and adapt this activity from the published instructions. One of the areas I'm excited to explore with them is how we can use AI to quickly transcribe, catalog, and summarize new contributions, so we can improve how we re-present the ideas to the next round of participants as they arrive moments later. Once we figure out how to do this well, could we use this activity as a way to better understand what a local community wants to see in a sustainable future? Can it serve as a structure or model for catalyzing a deeper conversation about how to get there?

If you are interested in hosting or building Solarpunk Futures in your library, science museum, school, or other institution, or if you'd like to support the continuation of this work through Playing with the Sun, reach out to me at: pwts (the little swirly "at" symbol) amosamos.net.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Ben Mardell and Amy Silver for advice and editing. Thanks to the members of the Experimenting, Experiencing, Reflecting Project, a collaboration between Studio Olafur Eliasson and Aarhus University, and the Carlsberg Foundation for supporting this work.