Singing, transgression, and rituals: Lessons about playful learning from my nieces’s weddings

Drawing on two joyful weddings that I attended this summer, this essay brings forward singing, transgression, and rituals as strategies to create playful learning experiences.

It might surprise you to find an essay grounded in two weddings posted on The Remake. I did not attend my nieces’ weddings thinking that I would be writing about them here, but on reflection there were useful lessons in the ceremonies for those of us who design playful learning experiences to build children’s solidarity with the natural world.

“Let’s play two”

When I was growing up in Chicago in the 1960s Ernie Banks was the city’s most prominent baseball player. The Chicago Cubs’s Hall of Famer exuded love of the game. For example, at the end of the first game of a double header, he would excitedly call out, “Let’s play two.”

This past summer I got to “play two” regarding family weddings. The first was my niece Ilana’s to my now nephew Adam. Three weeks later Ilana, who is a rabbi, was the officiant at Emma and Matt’s wedding.

The weddings were far from carbon copies of each other. Ilana and Adam’s wedding was held in a city. Emma and Matt’s wedding was in the countryside. Ilana and Adam’s ceremony was held inside. Emma and Matt’s ceremony took place outside. The night before the wedding, guests to Ilana and Adam’s wedding were invited to a havdalah (a ritual held at the end of the Jewish sabbath). The morning of Emma and Matt’s wedding guests were invited to go on a hike.

There were similarities too. Putting an egalitarian spin to the Jewish tradition of the bride circling the groom seven times at the start of a wedding ceremony, the brides and the grooms circled each other three times, and then circled together to make the seventh rotation. Each had a tisch, a ritual which I will explain below. In these moments of celebration, the brokenness of the world was acknowledged.

And both weddings were very playful. Elsewhere I’ve written about the importance of playfulness; how it is a mindset in which one is inclined to see situations and activities as containing the possibilities for agency, wonder, and delight (dimensions of experience that enhance learning). A playful mindset is the active ingredient that turns activities and other experiences into play. For example, while the game of baseball is not enjoyable or fun for everyone, and spending the day at Wrigley Field was work for some of the Chicago Cubs, Ernie Bank’s approach to double headers turned them into occasions of play. While the weddings were not intended as educational experiences, the singing, invitations for transgression (breaking of rules), and deployment of rituals that built on but were not bound by tradition turned these two weddings into occasions where the couple and their communities experienced agency, wonder, and delight. They thus hold lessons for those of us who want to create playful learning experiences for children and adults.

Singing

In Denmark, one of the happiest countries in the world, people regularly gather before work to sing. “Morgensang” has its origins in the thinking of N. F. S. Grundtvig, who believed that singing fosters the sense of community needed in a democratic society. One is more likely to get into a playful mindset–to feel one can take risks and even be a bit silly–if one feels the trust engendered by a sense of community.

There was a lot singing at the two weddings. At the ceremonies and services, we sang Jewish prayers. On the dance floor, we sang familiar pop songs. Adam loves sea shanties and so we learned and sang Stan Roger’s Northwest Passage, a wonderful song for a group to sing together. As I looked into strangers’ eyes as we belted out Roger’s lyrics about the Franklin exhibition, smiles were exchanged. Connections were made.

Singing and music have long been a staple of early childhood classrooms. Several generations ago it was a requirement in many teacher training programs to learn how to play the piano in order to lead children in song. Singing continues today, though more often aided by stream services. Which is fine, as long as the children’s voices can still be heard.

While we often sing with children, American teachers rarely sing together in groups of adults.

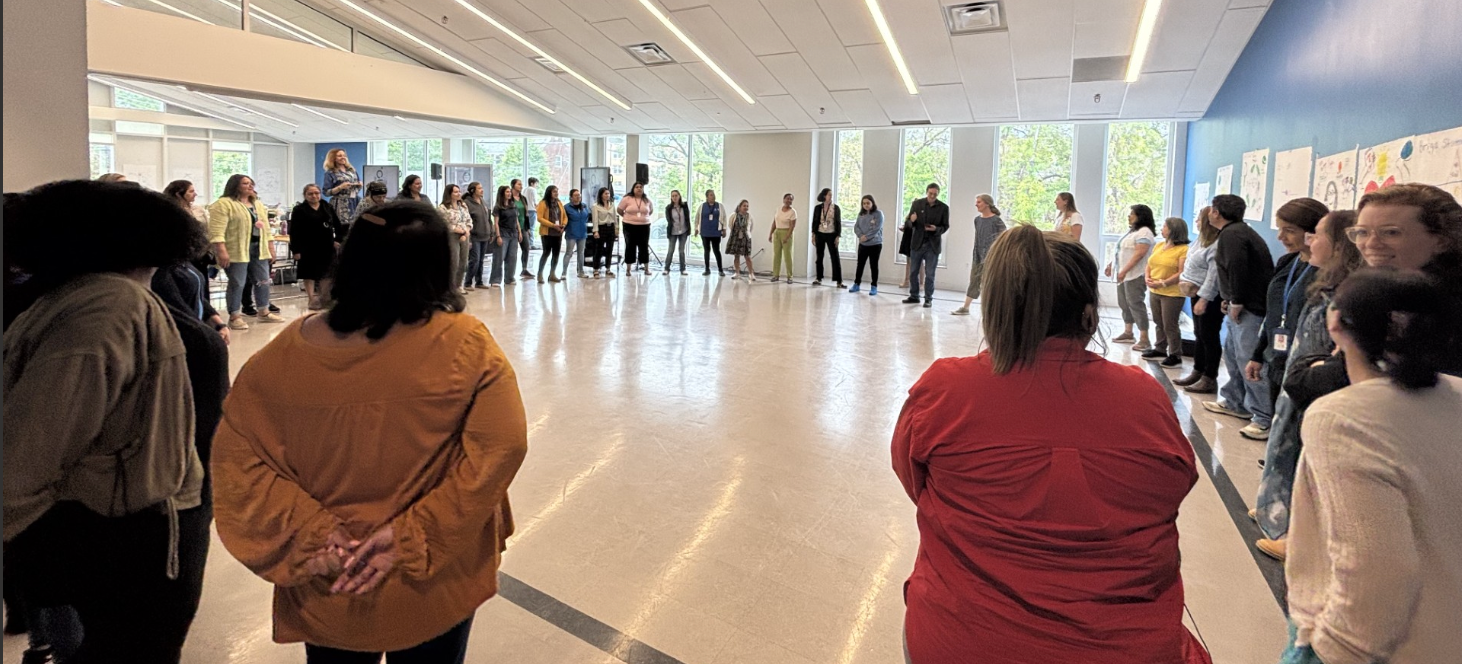

I recently started experimenting with singing in the professional development sessions I lead. Noting that energy often flags in the afternoons, I gathered the group together in a circle, explaining that I had an easily learned song for us to sing together. The tune, Brian Eno’s I'll Come Running, begins with poetic lyrics. After about a minute Eno gets around to what he’ll come running to do: “I’ll come running to tie your shoes.” After smiling and a bit of hesitancy, most participants happily sang along to the repeated line.

Based on my experiences, I would encourage others to give singing a try as a way to infuse playfulness into professional development sessions. Of course, you should pick your own tunes.

Another time people sang together was at the “tisch.” Let’s now turn to this ritual deployed at some Jewish weddings and its transgressive nature.

Transgression

But first, let's talk about playfulness and transgression. It is a mistake to think that play has no rules. Play does, it is just that the players get to make up and change the rules. They even break them. Getting to make, change, and break rules is agentic and thus conducive to a playful mindset.

Danish is helpful here to understand the relationship between playfulness and transgression. The Danes have two words for play. Spil refers to play with rules. Think organized soccer, chess, and those very prescribed Lego kits with pages worth of directions. Leg refers to play where the players create their own rules: the dramatic play of preschoolers, the pick-up game of baseball where there are only 7 players and so rules need to be improvised, and teenagers having a garage band session. The need to adhere to rules can kill a sense of playfulness while the ability to create rules can enhance playfulness.

Now to the tisch, a Yiddish word which literally translates into table. Before Ilana and Adam’s wedding ceremony, they each sat at the end of a long table along with 30 of their friends and family. Many others stood around the table. The tisch began with a friend explaining that the couple would be giving a “divar torah”, a lesson about the week’s biblical passage, and that “under no circumstance should they be interrupted.”

But interrupted they were. A talk that, if uninterrupted would have taken five minutes, lasted an hour. Adam began the divar torah by noting that “It’s so wonderful that we are all together.” The word “together” was the trigger. He got no further as the group broke into the Beatles “Come Together.” As Ilana took over the divar torah there were more interruptions; more Beatles tunes, Taylor Swift songs, and Passover prayers interrupted the couple. There were laughter and smiles. Ilana and Adam were in stitches.

Why was the ritual so fun and playful? Singing helped. So did the breaking of the rules; doing things that we weren't supposed to do. Interrupting someone giving a divar torah; not done. Being rude to the bride and groom on their wedding day; unheard of. But here we were, interrupting Ilana and Adam at every opportunity we had. The transgressive nature of the tisch created a very playful mindset among the participants. We were playing.

In school, children generally do not get to make rules, and if they break the rules, there are often negative consequences. While my colleagues and I appreciate that young children like to be silly, we are often frustrated by children becoming “too silly”, derailing conversations at gatherings. Certainly part of our job is to help children learn when and how to be silly and when to reign it in.

What about learning for adults? I have never been to a professional development session where breaking rules, such as interrupting the speaker, was encouraged. The tisch has me asking how transgression might be deployed in educational contexts to promote playfulness for educators.

Rituals

I have a dear friend who hates religious rituals, arguing that they are empty and meaningless. I can understand why he feels this way. We met, now over fifty years ago, at the Jewish day school which I attended from 4th through 8th grade. One of our shared experiences at the school involved the birkat ha mazon, the prayer recited after meals.

The schedule at the school was that after lunch we went outside for recess. The birkat ha mazon was what separated my friend and I from our favorite part of the day–football. In performing the ritual prayer we faced a delicate balance. We wanted to say the prayer quickly so as to get outside. But if we said it too quickly, the teachers might have us repeat the prayer, eating up precious play time. There was one way to say the prayer correctly and we had no say in the matter.

Despite this experience, I feel it is a mistake to abandon rituals. There is an undeniable power in the rituals. Built over centuries and more, and practiced by people around the world, rituals can have a “thickness” or staying power. When those involved have a sense of agency in a ritual, it can be playful and hold meaning.

Let me describe Emma and Matt’s tisch to explain. It was very different from Ilana and Adam’s. Rather than 30 people at the table, there were eight. Rather than a divar torah, there were toasts and songs led by a friend playing the guitar. There were no interruptions. There was a Beatles song; Matt played In My Life on the guitar as we all sang along. And like Ilana and Adam’s tisch, there were smiles and laughter. It was a joyful, playful affair.

Ilana and Adam and Emma and Matt had lots of say in how their tisches unfolded. They worked with friends to craft a ritual that built on traditions developed over thousands of years. They approached the situation with a “more than one way” attitude. For example, they changed the traditional tisch from a male-only affair to an egalitarian occasion. Their choices reflected their values, personalities, and communities. To this day I am allergic to the birkat ha mazon. After this summer, I love tisches.

How might we go forward in creating rituals with children that hold this power and connect them to nature? I end this essay with a thought experiment that addresses this question.

Rituals for a sustainable future: A Thought Experiment

Newtowne School, where I work, has lots of traditions and rituals. We have monthly “All-School Gatherings.” We begin the year with a family meeting for the children’s grown-ups. We end the year with children, teachers, and families watching a slide show put together by our director Caitlin featuring each child at the school.

Each November we have a “Lantern Parade.” The Lantern Parade begins at 5:30 pm as children and their families return to the school just as it is getting dark. In a room festooned with lights, the community eats together.

Some children wear costumes.

There is play with lanterns and other lights.

At the appointed time, we all leave the school and parade over to a park across the street.

Members of the community who play guitar lead us in a few songs,

and then families head home for bed.

Over the last couple years I have helped add two new components to the Lantern Parade.

The Green Dragonflies, children in the oldest class who are turning five, take photos during the evening that they use to create a slide show that is sent out to families before the Thanksgiving holiday a few weeks later.

I also set up an activity for children and families connected to the curriculum. This past year the activity involved “Leaf People” which you can read about in a previous Remake essay.

The thought experiment: What might be added to the Lantern Parade that would help foster our community's connection to the rest of nature? My initial brainstorm includes:

- At the park, singing under a tree that the children have selected. Before the advent of large buildings in our area, both before and after European colonization, rituals and meetings were held under designated “gathering” trees. For our monthly All-School Gatherings we have embraced this practice, sitting around a “tree” with branches representing each classroom. Bringing this practice to the Lantern Parade could make a connection between trees and the entire school community.

- Take advantage of the dark. The Lantern Parade is a rare instance when children and teachers are together at night. Last year, the moon rose as the children headed for home. Nighttime also brings out certain critters. This summer I attended a Moth Ball, complete with screens and lights to attract insects to observe. While fewer insects will be about in November, I wonder how we can take advantage of the dark to connect to nature.

- Consult with a Native American elder about possible appropriate traditions to include in gatherings in the late fall. In a recent post I discussed how conversations with an elder might help children learn who has lived in our city and help them make connections with the rest of nature.

- Involve the children in the planning. Historically, a group of parents have planned out the Lantern Parade (we are a family co-op). For the last two years I’ve joined the conversations regarding what activity to include. This coming year I hope to involve children more in the planning so they can experience the agency involved in helping to craft rituals.

I hope this thought experiment will, for us at Newtowne, spark conversation about this coming year’s Lantern Parade. For others, I hope it will start conversations about what rituals you might create at your program, with your family, or in your community that builds solidarity with nature. As you plan, don’t forget singing and transgression.

Ilana and Adam and Emma and Matt, mazel tov. Thank you for creating such beautiful, playful experiences for your family and friends.

Credit to Mitch Resnick, who in his book LifeLong Kindergarten, writes about the distinction in Danish between spil and leg (the writer Michael Chabon makes the same point in his Manhood for Amateurs). Thanks to Liz Merrill and Caitlin Malloy for their always helpful comments on previous drafts of this essay.