Including First Nations Perspectives at Newtowne: Provocations from Australia

Reflecting on practices in early childhood programs in Australia, this essay shares my initial thinking about bringing First Nation perspectives into teaching and learning at Newtowne. Writing this essay is my way of making sense of my trip to Australia. Publishing it is an invitation to engage in dialogue.

The Wild Turkeys of Cambridge

In a previous essay I shared a conversation among three Green Dragonflies (five- year-olds) about the Wild Turkeys that live in Cambridge. The Turkeys are a source of controversy among my fellow Cambridgians. Some folks love them and follow their movements on a Facebook page. Some hate them as they are big, can be aggressive, and snarl traffic as they leisurely cross the road. The children understood the complexity of the situation, wanting to have people feel safe and, at the same time, not wanting harm to come to the Turkeys. And they were under the impression that the Turkeys roaming around were escapees from farms. They advocated that the Turkeys be removed from the city and placed in safe, comfortable cages. I wonder if the children’s opinion would have been different if they knew that the Turkeys were here long before Cambridge existed.

Of course, it is not just the Turkeys. The place now called Cambridge looked very different in 1619—the year before the Mayflower (the ship that brought the first European settlers to this area) landed. There were different plants and animals, more ponds and streams, and far fewer human-made structures. The people who lived here had a very different relationship with the rest of nature, a relationship current-day residents could learn from as we strive to create a more sustainable way of life.

In March, I visited Australia and was impressed with the Aboriginal presence in the culture generally and in early childhood settings in particular. I learned of an early learning center in Melbourne where an elder of the Wurundjeri people joined with teachers in a research project that engaged children in “making kin” with the rest of nature. I returned from my trip wondering how we at Newtowne could engage in Native American perspectives in order to help understand who was here before us and build solidarity with the rest of the natural world. In this essay, I share what I encountered in Australia and what I am taking away from the trip.

The Aboriginal Presence in Australian Culture

Landing in Sydney, I was immediately struck by the presence of Aboriginal culture. There was an Acknowledgement of Country (what in the US we call a Land Acknowledgement) in a parking lot I walked through on the way from the airport train to the hotel.

There was an Acknowledgement of Country on the commuter train I took to see friends who live north of the city, and at a pool I swam in.

In public spaces, where the Australian flag was flown, the Aboriginal flag was almost always present.

As the poet T.S. Eliot explained, by “making the familiar strange”, visiting another country can serve as a mirror in which we can see our own culture more clearly. For someone like me who lives in a wealthy, western city by the ocean in a place colonized by the British, there was much about Sydney (and Melbourne and Hobart) that felt familiar. But not completely familiar. The acknowledgement of Aboriginal people in these places raised questions about the relative absence of Native Americans in Cambridge.

These questions led to many conversations with Australian friends and colleagues. I learned that representation and respect given to Aboriginal people is relatively recent and far from perfect. Many pointed to the place of Maori culture in New Zealand as an example that they wanted to follow. Despite the imperfections, the mirror Australia provided shook me into thinking about practices back home.

The Aboriginal Presence in Early Childhood Settings

The Aboriginal presence extended into early childhood settings. Each day of the conference I attended began with a “Welcome to Country” from an Aboriginal elder. These welcomes were, as advertised, welcoming. They were also gently educational. I learned the names of the local nations (there are over 250 Aboriginal nations in Australia), heard some of their language spoken, and was reminded that their ancestors had lived on this land for over 60,000 years. Almost all the presenters that followed gave an Acknowledgement of Country, including those from First Nation groups from outside of Sydney. I appreciated the reciprocity of this exchange.

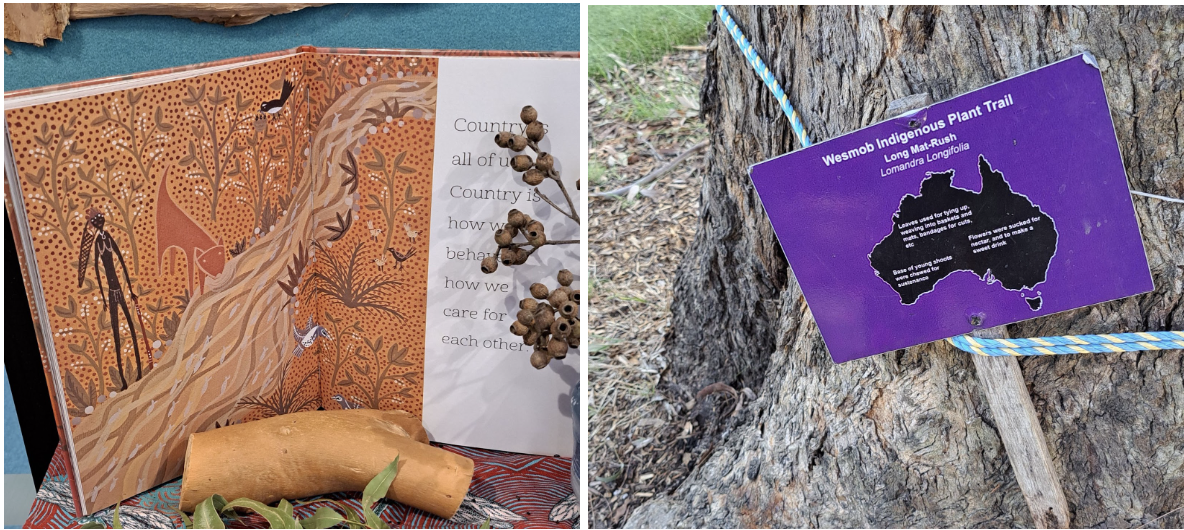

The schools and early childhood centers I visited had First Nation artifacts on display, including: books, Aboriginal flags, and information on trees in the play yard regarding their connection to Aboriginal people.

In several schools, as part of the daily routine, children made Acknowledgement of Country that they and their teachers have fashioned. For example at Wesley College in Melbourne the children in one classroom say:

We at Wesley College would like to say thank you to the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation for sharing your land with us. We promise to look after it. The animals and people too. Hello land. Hello sky. Hello friends.

As someone committed to promoting children’s solidarity with nature, I was excited about a daily promise to look after the land, seeing the Acknowledgments as opportunities to open up valuable conversations. Given the brutal history of colonization, these recognitions are important in their own right.

I also learned that it is common for Aboriginal elders to visit early childhood programs. They share stories and songs. Some use a set curriculum about the Indigenous people of the area.

The educators I spoke with were supportive of these visits, though noted that, depending on the elder, children’s engagement varied. They also explained that the visits, disconnected from the rest of the curriculum, could feel tokenistic. In light of this context, I was particularly impressed by a research project at MLC Kindle, an early childhood program in Melbourne.

Making Kin: Research at the MLC

Making Kin: Care and Ethical Obligations in Inter-creature Relationships is a teacher-research project that took place at the MLC Kindle. MLC Kindle serves children six weeks to five years and is part of the Methodists Ladies College, a Kindergarten through 12th grade independent school. The research team–the educators at MLC, Stefania Giamminuti of Curtin University in Western Australia, and Murrundindi, Ngurungaeta (leader) of the Wurundjeri people– explored how to understand and foster children’s interest, care, and solidarity with the rest of the natural world. They incorporated an Aboriginal perspective and deployed documentation practices developed by educators in Reggio Emilia, Italy, in their research. I learned about Making Kin through conversations with members of the research team and an hour-long video that they generously shared with me (Giamminuti, S., Polson, S.A. (2023). Making kin: Care and ethical obligations in inter-creature relationships [documentary film]). My colleagues are working on making this film publicly available.

The overarching research question–what does making kin mean to young children and what is a community–promoted a number of interrelated investigations. Children got to know Oak trees, Possums, and water (focusing on a nearby river).

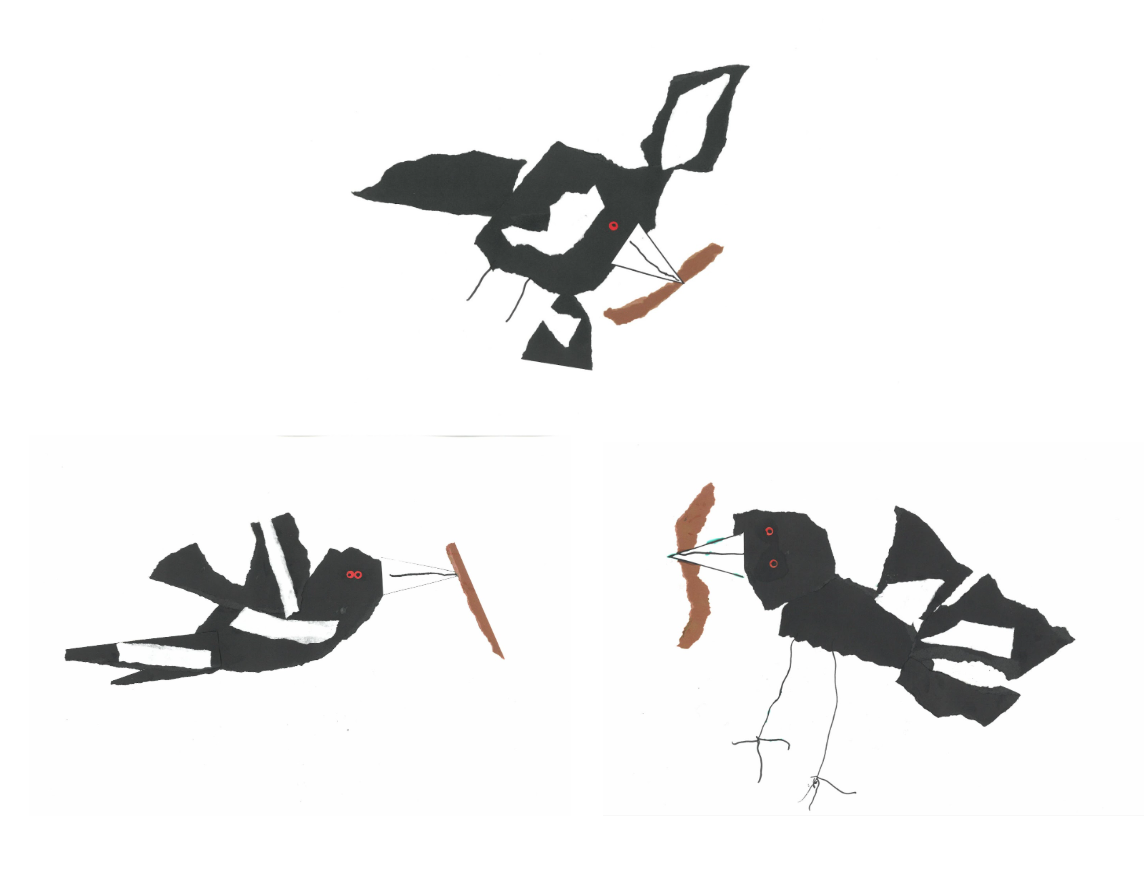

An inquiry into Magpies and worms is emblematic of these inquiries with children exploring important ethical questions and producing beautiful art. The inquiry began with the children’s curiosity about the Magpies that were visiting their play yard. Noting this interest, Murundindi told the children stories about Magpies and taught them songs about the birds. The teachers helped the children make Magpie puppets to play with and provided collage and other materials to represent the birds. They noticed the Magpies ate worms and, at one point a child expressed a desire to protect the worms. An important ethical question was thus raised. Do they help some friends find food or do they protect other friends from being hunted? A big and engaging question with no one answer. A question that invited conversation and where a child and an adult’s point of view were equally valid.

There are many factors that created the conditions so that children at MLC Kindle could make kin with Magpie and Worm. Those familiar with the Reggio Approach will appreciate that: children had a host of materials and activities which to explore and get to know the rest of the natural world and to think with including puppets, poetry, paint and play; time for the research to unfold (this was a two year project); an understanding of early childhood centers as places of research; and “pensiero progettuale (design thinking)”--a cousin of emergent curriculum and project based learning– in navigating between children’s interests and agency and adult learning goals.

I want to highlight something that was new to me: bring an Aboriginal elder into conversations with other educators that were grounded in pedagogical documentation. It is important to know that Murrundindi had been coming to the MLC for over 20 years; the research drew on a long and respectful relationship. And during the Making Kin project Murrundindi, Stefania, and the MLC educators grounded their conversations in documentation of the children’s thinking–video of children at play, transcripts of group conversations, and drawings among other artifacts– to plan next steps for the inquiry projects. Murrundinidi shared his perspectives in these conversations and adapted his classroom visits to match the children’s interests.

So the Making Kin project was theoretically sound. What about the results? Engagement is how I evaluate success of the sessions in my studio at Newtowne. Was I able to identify an interest of the children? Did I frame the activity in a way that made sense to them? Were the materials provided compelling? Did the children learn with and from each other? In pursuing my learning goals, were the children able to do what they wanted?

From the available evidence, the children at MLC Kindle were engaged. Watching the video I saw their focus in play and in conversations with adults. The high quality artwork could have only been produced by children who were invested in their work. Two other data points. The first from a parent who noted:

We speak of Murrundindi often. The children are so interested in him coming to class…Sometimes at home it takes a bit of prompting, “what were some things you did today?” But without fail they volunteer Murrundindi has been there.

And Murrundindi, who visits other schools as well, was also struck by the children’s engagement:

The kids’ engagement [versus other centers] is completely different. Doing that research online and putting it into practice, when I come into the center…You can see that the children are more interested. They want to know. They want to learn.

For the past two years I have worked to foster the children at Newtowne’s solidarity with nature. I clearly have much to learn from the Making Kin research. For those who want to learn more about this research, the team has a forthcoming chapter in Z. Andreadakis & C.T. Oropilla’s Confronting the Polycrisis: Contributions from Early Childhood Education and Care for Sustainable Futures titled “Troubles, enchantments, and ethical responsibilities in inter-creature relationships: Children and educators welcoming indigenous knowledges and care.” The book will be published by Springer.

Back home, now what

I returned home full of energy that I knew had to be tempered with patience. My desire to incorporate lessons from the MLC research at Newtowne requires collaboration with colleagues, families, and Native American elders. I needed to clearly articulate my vision, marshal resources, build relationships, and be open to the input of others.

The first step was obvious. Knowing that she would be supportive and helpful, I strategize with Newtowne’s director Caitlin Malloy on how to move forward. She helped arrange times where I shared my thoughts with the staff, families, and the wider Cambridge early childhood community. These conversations have led to connections with Native American elders. Simultaneously, Caitlin considered how to find the resources needed to support such a collaboration.

I also knew I needed to learn more about the history and current context of Native Americans. My Newtowne colleague Jen Schreiner alerted me to the online course Native American Studies for Everyone led by Anna West of the Chickadee Community Services in Montana. The course is engaging and informative and includes practical advice on connecting with Native Americans to support classroom endeavors.

Interesting side note: Montana is a particularly rich place to look for resources in this area. In 1972 the state enshrined in its constitution that every Montanan should learn about the distinct and unique heritage of American Indians in a culturally responsive manner. Their statewide effort, Indian Education for All, provides knowledge, skills, and content in this regard.

All told, seeds have been planted that I hope will begin to germinate when school opens in September.

The Flying Foxes of Australia

For someone interested in the natural world, Australia is a treasure chest. I was able to go out in the bush where I encountered critters I had previously only seen in books: wallabies, kookaburras, and three foot long Monitor Lizards. But my most exciting critter sighting occurred in the heart of Melbourne. Walking through the city’s botanical gardens I saw what I first took for a crow. It was big and black, but did not fly like a bird. It flew like a bat. It was, in fact, a bat, a member of a Flying Fox colony that had bedded down for the day in a grove of nearby trees. Finding the grove, I spent an hour watching and listening to these impressively large creatures (wing spans up to 5 feet) as they hung upside down, resting, grooming, and occasionally taking flight.

So when a package arrived at Newtowne from colleagues at MLC Kindle I was delighted that it included Debra Bird Rose’s Shimmer: Flying Fox Exuberance in Worlds of Peril, a central text in their research project. Rose was an anthropologist and posthumanist thinker. In Shimmer I learned that, similar to the Wild Turkeys in Cambridge, Flying Foxes are a source of controversy. They can be loud and eat fruit intended for human consumption. As a key pollinator, they are also an important part of ecosystems. In flight, they inspire awe. Rose shares stories of caring, general indifference, and tremendous cruelty directed towards Flying Foxes by the descendents of European settlers.

She also describes the relationship between Flying Foxes and the Aboriginal people she lived with and learned from in Northwest territory settlements of Yarralin and Lingara. The people of these communities see Flying Foxes as mindful creatures with their own foods, foraging method, language, being together, ceremonies, and humor. They see the Flying Foxes as kin.

To help frame the relationship between the people and bats, Rose invokes the philosopher Lucien Levy-Bruhl who, after reading the reports of anthropologists that had fanned out across the world at the start of the 20th Century, concluded that Indigenous thought involves a logic of connections between people and their environment that is coherent as any western logic. Rose explains that the Indigenous people of Australia’s elaborate system of multispecies kinship, which she learned about in Yarralin, is an example of such logic.

Reading about how, in their stories, ceremonies, and customs, the people Yarrallin and Lingara understand their connections and obligations to the rest of nature, one can appreciate this claim. In seeming recognition that an individual has a finite capacity to care, Rose describes a system where, “The responsibility of care is spread across many species in a structured manner in a way everyone can benefit from.” For example, based on matrilineal descent, some in Yarrallin are Flying Fox People, some are Emu people, some are Possum People (and more), with special responsibilities towards these critters. Based on gender and family background, each person has other responsibilities to places and parts of the ecosystem. As a Flying Fox person is prohibited from marrying another Flying Fox person, responsibilities are dynamic across families. And there is an underlying ethos not to be wasteful or disrespectful to any part of the world.

So to return to the questions facing children at MLC Kindle and Newtowne. Magpies are our kin and so are worms. Do we help feed Magpie or protect Worm? Wild Turkeys are interesting and disrupt human activities. Do we let them roam around our city or place them in comfortable enclosures? Are these the only ways to think about these questions?

In the entangled world our children will inherit–a world where they will constantly face ethical challenges about balancing the needs of different creatures in stressed ecosystems–learning the wisdom and logic of the people who lived here before us, whether the Wurundjeri people or the Massachusetts tribe, feels invaluable. Not just to help them live an ethical life, but to help them fashion a more sustainable way of life in a time of rapid climate change.

Thanks to my hosts in Australia: the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation (Sydney), the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation (Melbourne), Palawa people (Tasmania) along with Anthony Semann, Cameron Paterson, Dave Runge, Katrine McNab, and Fiona Zinn. A huge thanks to the members of the Making Kin research team for generously sharing their work and to Natalie Jones, Sally Polson, and Stefania Giamminuti for sending me Shimmer. And thanks to Amos Blanton and Caitlin Malloy for their ever thoughtful feedback on this essay.