Children are scientists with hypotheses: More Playing with the Sun at Newtowne School

This essay describes a session where two- and three-year-olds explore a solar powered Merry-Go-Round created from the Playing with the Sun kit, documenting how these materials create opportunities for hypothesizing and experimentation.

The title of this essay expands on a famous saying of Loris Malaguzi, the founder of the Reggio Approach: The infant is a scientist with a hypothesis. Recently, I saw such scientists at work at Newtowne in session with children from the Purple Fish class. As the children explored a solar-powered Merry-Go-Round, they acted as a research group, making and testing numerous hypotheses.

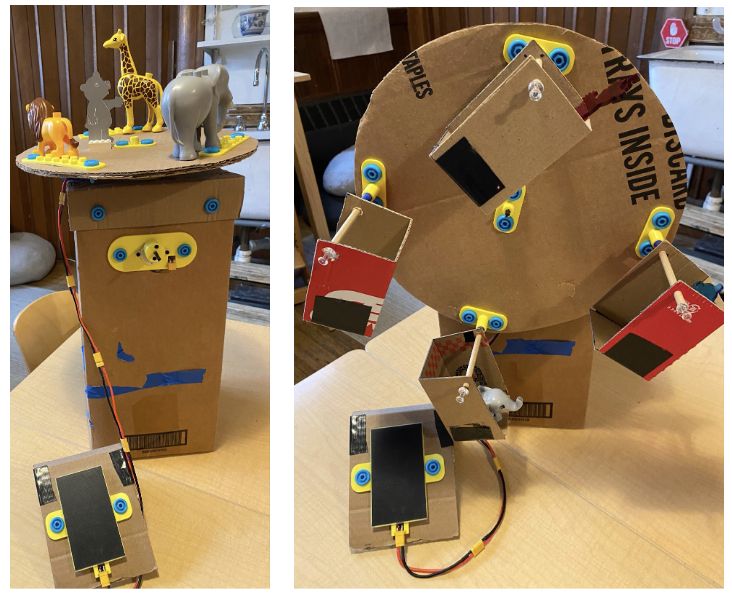

The Merry-Go-Round is constructed out of cardboard and components from the Playing with the Sun project that were created by Robbie Berg. Playing with the Sun is an open-source project to develop creative learning activities that use sustainable energy. We are exploring how a new collection of prototype materials might create opportunities for hypothesizing and experimentation by young children. In a previous Remake essay, I shared how four- and five-year-olds’ began to understand the workings of solar power. In this essay, I share a description of a half-hour exploration of the solar powered toy by two- and three-year-olds, and comment on the role of the teacher in supporting the research of groups of young children.

“How can we make it go faster?”

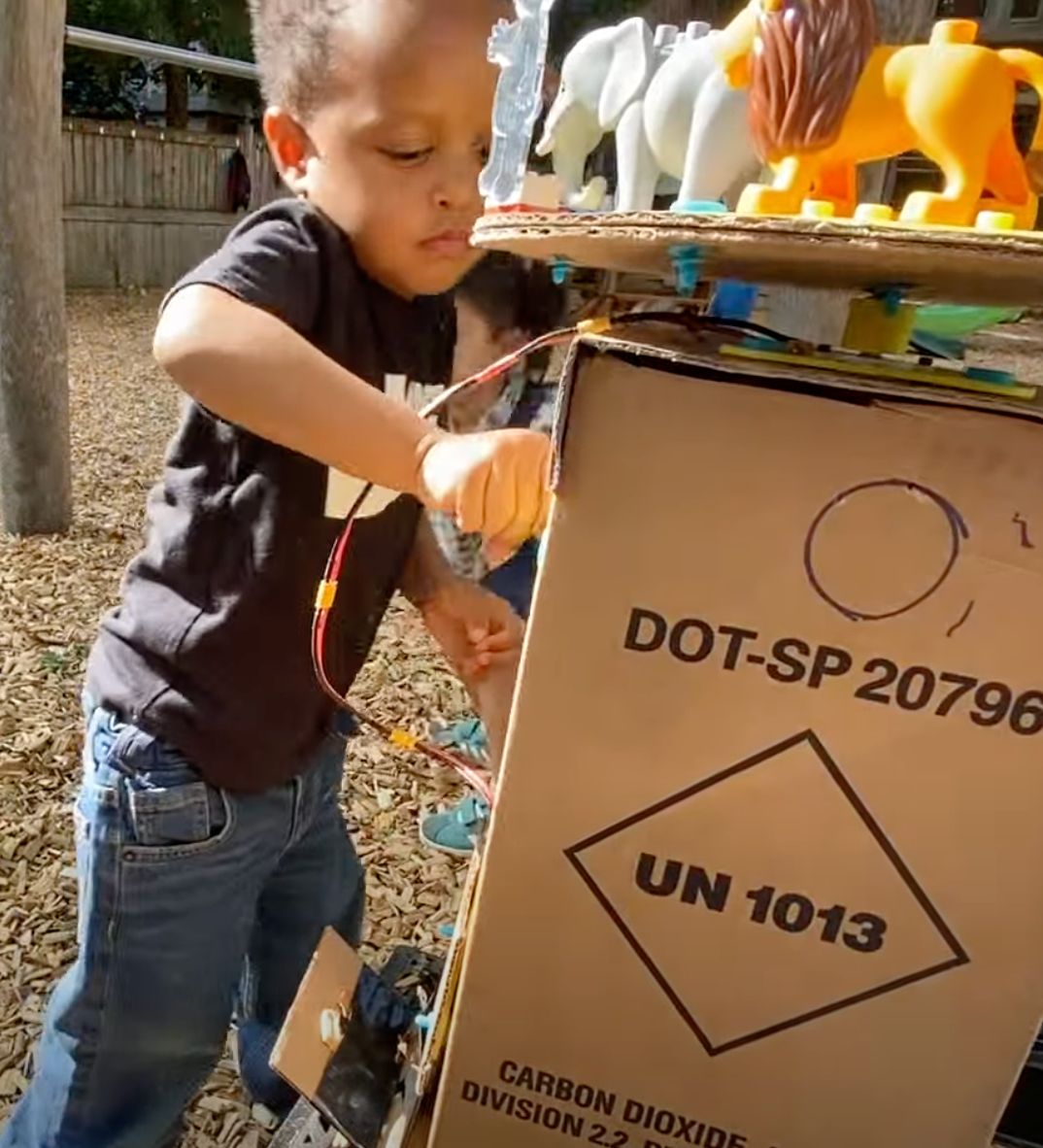

On a sunny morning in early October, I brought the Merry-Go-Round to the playground where the Purple Fish were happily engaged in a variety of playful activities: cooking in the mud kitchen, climbing on the monkey bars, playing hide and seek, and more.

The Merry-Go-Round immediately garnered the interest of six children (half the class).

The children’s attention is drawn to the top of the machine. When I ask “what do you notice?”, they reply:

Averil: Lion.

Malanka: Elephant.

Rachel: Bears.

Victoria: Giraffe.

When two more children join the group and inadvertently cast a shadow on the solar panel, the Merry-Go-Round slows down.

Kelly asks, “How can we make it go faster?”

Victoria has an idea. Raising her finger to make her point, she declares: “Acorns.” I respond: “We could try. Does anyone have an acorn?”

Maria has one, and she carefully places it on the Merry-Go-Round.

The children watch the acorn as it spins around, but the Merry-Go-Round does not speed up.

Victoria suggests another acorn. Kelly and Richard go off to find more. They soon return and place more acorns, putting them on the Merry-Go-Round to test the hypothesis. The Merry-Go-Round does not speed up.

Victoria has another hypothesis. “Maybe this,” she wonders, and places a pinecone on the Merry-Go-Round.

Another hypothesis tested and disproven.

The children’s interest turns to the animals getting a ride and they spend a few minutes taking them off and putting them back on the Merry-Go-Round.

Averil notices the solar panel. After considering it for 30 seconds, she puts it back down.

To refocus the children on Kelly’s question I ask, “What else could help the Merry-Go-Round move faster?” Victoria speculates, “ Maybe a ball” and places a small ball and places it on the Merry-Go-Round.

When this does not change the speed, she places a second ball on the platform. Maria suggests a bigger ball and the smaller balls are replaced with larger one.

Laura suggests that wood chips might help. To test this hypothesis, Malavika, Laura, Rachel, Brian, and Petios begin putting woodchips on the Merry-Go-Round.

Then more wood chips. And more.

After noting wood chips have not helped speed up the Merry-Go-Round, the children remove them.

Twenty minutes have gone by and at this point the solar panel is reoriented to face the box. Without any light hitting the panel, the Merry-Go-Round stops. Most of the children leave for other play. Impressed by the length of time they have spent experimenting, I do not try to reengage them.

Petios, however, continues to tinker, determined to make the Merry-Go-Round spin.

He turns a cylinder on the side of the box that is part of the motor that powers the Ferris Wheel.

When this does not work, he wonders what else he might do.

I ask Petrios and Malavika, who has joined him, what they think: “Why has the Merry-Go-Round stopped?” Malavika suggests, “Maybe because someone knocked off the woodchips.” She then adds, “I don’t know why it isn’t working.”

I suggest, “Maybe because the solar panel is turned around.”

Petios considers the panel and fiddles with the bolts holding the panel to its cardboard stand.

Without success, he eventually moves on.

Rachel returns. She reorients the panel to face the sun.

The Merry-Go-Round starts revolving again and she states matter of factly, “ I made it work.”

I ask her how she did this and she says, “I moved my leg this”, demonstrating the motion she attributes to her success. Is she pulling my leg? I am not able to find out because it is time for the Purple Fish to return to their classroom. The experimentation, for now, has ended.

The role of the teacher

The Purple Fish’s session with the Merry-Go-Round makes me happy. Happy because these two- and three-year-olds were deeply engaged in an activity for a significant amount of time. Happy because the children were collaborating, listening to each other, and working together to answer a question. Happy because the session gave these children much agency. They could come and go as they wanted and try out their own ideas. Happy because the children were exploring new concepts. Happy because the children were happy.

The session meets the definition of playful learning, which I understand as children doing what they want to be doing, which is exactly what their teachers want them to be doing. What did I want the children to be learning during the Merry-Go-Round session? My learning goals for them were multiple. I wanted them to experience the value of learning from and with peers. I wanted them to feel empowered and take risks. I wanted them to feel good about their discoveries, what Eleanor Duckworth called “the having of wonderful ideas,” which she saw as the basis of intellectual development. I also want children to become familiar with the affordances of solar power as this is an increasingly important source of energy.

If learning about solar power was one of my goals, why didn’t I just tell the children how to get the Merry-Go-Round to go faster? My reasoning follows Malaguzzi's insight that every time we show children how something works we rob them of an opportunity to discover. And I am confident, based on their high level of engagement during this initial session, that the Purple Fish will continue their research and, in time, come to an understanding of how solar power works. My role as a facilitator of this group of young scientists involves thinking about how to help them continue and extend their explorations.

What's next?

In thinking about how to help children’s research to go forward, I find it fruitful to talk with colleagues, grounding our conversations in documentation. That is what I did with the Purple Fish teachers Jenna Rounds, Sam Liptak and Franny Alani and my Playing with the Sun friends Amos and Robbie, sharing the documentation presented above. Two ideas have emerged.

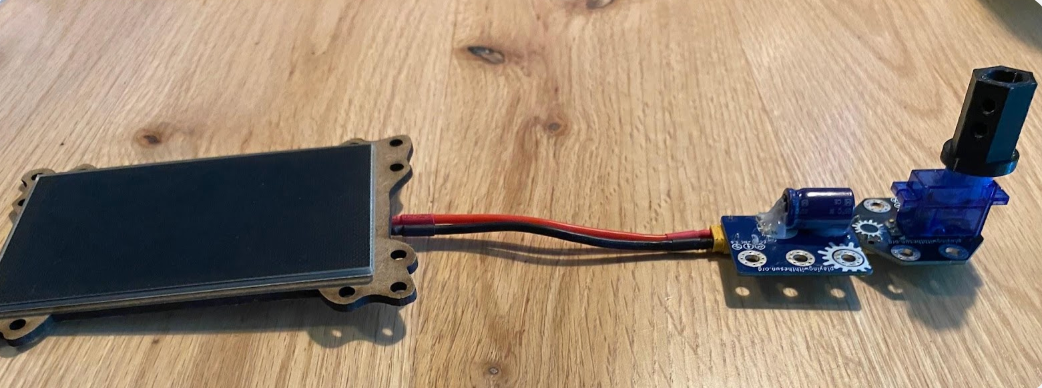

The first is to present the children a simple solar panel-motor set up along with the Merry-Go-Round. The Merry-Go-Round, and its companion Ferris Wheel, are engaging to young children, and have variables that can lead to misconceptions. For example, when I shared the Ferris Wheel with some Green Dragonflies (older four-year-olds), one thought the wheel was not moving because only three of the four cars had Duplo animals in them. She hypothesized that to make the machine move the fourth car had to be occupied. A solar panel connected to a motor may make the relationship between light and movement clearer to the children and they may transfer their understandings to the Merry-Go-round.

The second is to provide situations that could help the children make the connection between light hitting the solar panels and the motion of the machines. Outside, sunlight is pervasive. While clouds and tree branches can change the intensity of sunlight, these variables are unpredictable and not easily controlled. We wondered about setting up situations where the children could control the amount of light hitting the panel. One option is using a lamp indoors. With a strong-enough wattage bulb, a lamp that children can turn on and off, could power the machine. There are also windows. Newtowne is located in an old church, and the library faces south. The sun shining through the library’s pane glass windows creates an array of different intensities of light which could be interesting to explore.

We have started presenting the Purple Fish with the lamp provocation. In the Studio, they have used a lamp to power the Ferris Wheel and noticed that turning the lamp on stops the machine.

In the classroom, the physical setup dictated that the lamp be placed out of children's reach above the Merry-Go-Round. Recently, Malavika asked her teacher Sam to stop the machine, and Sam replied, “How can I stop it?” Malavika answered matter-of-factly, “Turn off the light” – a finding that can be shared among the research group.

Many thanks to Sam, Jenna and Franny for their collaboration in supporting the Purple Fish research group, Robbie and Amos Blanton for their material and intellectual support, and Caitlin Malloy for her careful read of a draft of this essay.